Series, Part 2: University of Hamburg Buildings in the Science CityInterdisciplinarity is key

8 August 2025, by Claudia Sewig

Photo: University of Hamburg / Engels

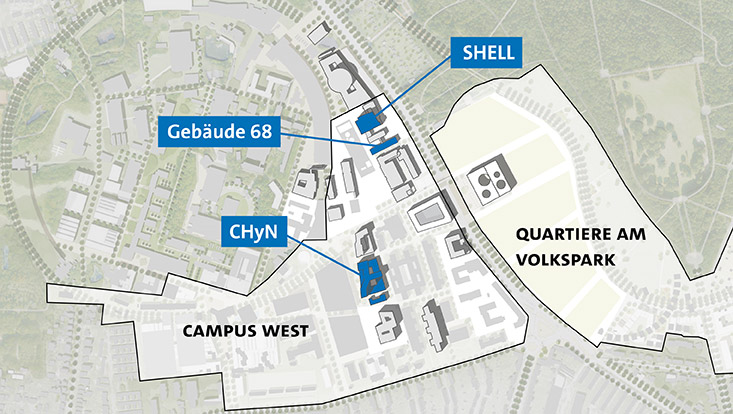

The Science City Hamburg Bahrenfeld is changing faster than any other research center in Hamburg. On occasion, we ask University of Hamburg members to introduce their workplace in existing or planned Science City research buildings and tell us what makes their building special. Today: the Center for Hybrid Nanostructures CHyN, the Shielded Experimental Hall SHELL, and Building 68, which is part of the Institute of Experimental Physics.

CHyN—home to the cleanest room in Hamburg

When it opened in July 2017, it caused a media sensation with what was probably the cleanest room in Hamburg—despite 628 holes in the floor. The latter ensure that the clean room of the University’s Center for Hybrid Nanostructures (CHyN) provides a virtually dust-free working environment by continuously extracting the air that flows into the room through the ceiling. This is extremely important when working with tiny nanoparticles, which are only a few atoms to 100 nanometers in size (one nanometer equaling one millionth of a millimeter).

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Parak is one of about 130 CHyN researchers. His Nanostructure and Solid State Physics working group at the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences develops materials for solving biological and medical problems. This is precisely what CHyN’s research is aimed at: analyzing the properties of solids and biomaterials and using them to develop new materials, among other things, to replace destroyed human sensory receptors with tiny bioelectronic implants.

Parak and his group are working specifically on the production of (nano)spheres made of gold: “These generate heat through light. Such beads could be absorbed by tumors, so that the heat generated by light would destroy the tumor cells. This would hold the benefit that only illuminated tissue would be destroyed, thus reducing side effects in other organs,” but this solution is still a long way off. “It often takes decades before ideas become therapies. My group conducts exploratory research, meaning basic research. We are investigating how the beads are absorbed by cells, what happens to them there and how we can use them to convert light into heat. Answering these essential questions teaches us where exactly to place the nanoparticles so they can benefit the body and help us understand and assess possible risks such as toxicity,” says Parak.

Interdisciplinarity is what Parak particularly appreciates about his work in the simple and modern-looking building, which, besides the clean room, houses 60 laboratories—some electromagnetically shielded or vibration-insulated. “Hamburg offers a very good infrastructure with a range of cooperation opportunities between the individual disciplines. Our working group includes physics, chemistry and aspects of biology, pharmacy, and medicine.” The group benefits from the important infrastructure provided by the CHyN, including cell culture and microscopes. Parak says: “There is no easy way to move cells from one building to another, it is thus important to have everything under one roof. For investigations which require X-rays, we can use DESY facilities. Almost all infrastructure we like to use is available in the Science City.” Therefore, this reason, most physics areas are already located in Science City. “We hope that other departments, such as Chemistry, will follow suit as quickly as possible, because this will further intensify our cooperation,” Parak says.

SHELL, where phone calls are impossible

The search for dark matter requires cosmic silence, ranging between one and 100 gigahertz (GHz is a unit in which alternating voltage or electromagnetic wave frequencies are measured). Therefore, experiments of the Excellence Cluster Quantum Universe are shielded by 3 meters of thick concrete and an additional Faraday cage in the walls of the Shielded Experimental Hall (SHELL) at Science City Hamburg Bahrenfeld to attenuate the power of a signal in this frequency range by a factor of 0.000000001. Protective measures thus make phone calls or short messages in the hall virtually impossible, as cell phones transmit in the 4 to 5 GHz range.

Of course, this is not intended to disrupt communication between researchers. “The measures are necessary to remove falsified or unwanted signals from our experiment in the search for extremely weak dark matter, which emits signals in this frequency range,” says Prof. Dr. Erika Garutti. Together with her team, the professor of experimental physics at the University of Hamburg and spokesperson for the Cluster of Excellence Quantum Universe is searching for new types of tiny elementary particles, known as axions, which presumably make up dark matter. This search is part of MADMAX (Magnetized Disc and Mirror Axion Experiment), which uses an amplified dielectric haloscope.

The SHELL Hall opened in 2019, was specially converted for this purpose. Before that, the bunker had been home to a so-called cyclotron. The particle accelerator was operated from 1969 to 2008. Initially, for nuclear physics work conducted by the Institute of Experimental Physics and from the late 1980s for medical research at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. But there are not only Quantum Universe researchers working here: In addition to DESY, university groups from Spain and France are involved in MADMAX.

“The enthusiasm, passion, and problem-solving spirit of researchers from all over the world and with very diverse skills” are a key location factor of the Science City Hamburg Bahrenfeld according to Erika Garutti. “You can find the right person to talk to about any technical or scientific question, and everyone is committed to finding solutions. With this power, you can move mountains . . . or even find the best-hidden dark particle in our Universe,” says Garutti.

Building 68 / Institute of Experimental Physics—60s clunker on the outside, a state-of-the-art heart

Inconspicuous on the outside. A 2-storey red-brick building with long corridors connecting mostly offices. “In the shadow of the impressive new buildings erected on this site, building 68 makes us feel a bit like working in that old, half-ruined house from the movie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which is also embedded into a modern environment,” says Prof. Dr. Gregor Kasieczka laughingly. This is what makes the Science City Hamburg-Bahrenfeld special: It is not a chain of new buildings only, but a long-established district where not every house reveals at first glance that excellent research is done under its roof.

Building 68 is just one of several Science City locations that provide a workplace for the over 250 researchers from the University’s Institute of Experimental Physics. As part of the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences and the Department of Physics, their working groups conduct research in accelerator, astroparticle, neutrino, particle, and detector physics as well as in gravitational-wave and photon physics.

The Particle Physics and Detector Development group, of which Prof. Dr. Gregor Kasieczka is a member, investigates the fundamental building blocks of matter, their properties, dynamics, and interactions. “My working group’s research involves developing new algorithms for physics research based on machine learning and artificial intelligence and applying them in the search for new physical phenomena in experimental particle physics,” says Kasieczka.

We aim to find out specifically, how large accelerator facilities, such as those at CERN near Geneva in Switzerland, can be used to learn more about the behavior of elementary particles. The physicist specifies: “When it is said that something has been ‘discovered at CERN,’ this is true insofar as the equipment is there, but the 3,000 researchers on the subject are actually scattered across the globe. Hence, a large part of the work is decentralized, for example, in our building 68 in Bahrenfeld.”

His office equipment deviates from that of a traditional experimental physicist who needs a large hall. “To me, whiteboards and coffee machines count more. And computers, of course, but these are housed by a computing center,” says Kasieczka. The Science City is a great place for particle physicists, as there are not only large University groups on the subject, but also the DESY research center: “As DESY originally evolved from particle physics at the University of Hamburg, it is more closely related to us than to other parts of the University.” This creates a unique scientific environment.

He hopes that, in future, the Science City will cultivate a thriving neighborhood: “We need pubs, cafés, and even more people. I hope that it will perk up, when more students flock to campus. Sharing ideas—this is even more important for my work than the existing hardware.

Science City Hamburg-Bahrenfeld

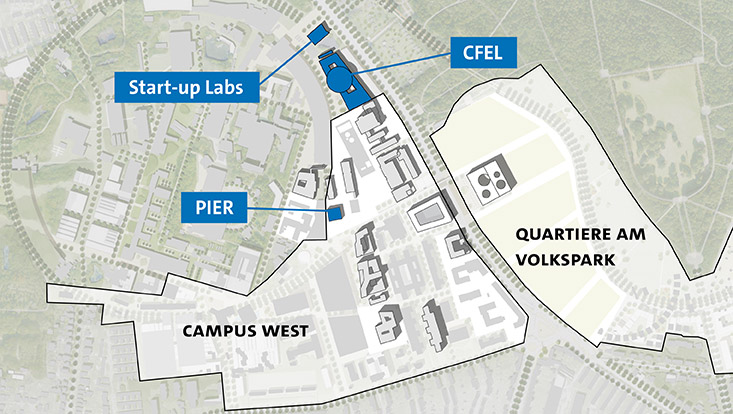

The Science City Hamburg-Bahrenfeld will eventually span 125 hectares in Hamburg’s western suburbs, right next to Altona’s Volkspark, a public park. Various renowned institutions, including DESY, the European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser GmbH, the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter, and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory already form a research campus. Two out 4 University of Hamburg clusters of excellence are located here: CUI: Advanced Imaging of Matter and Quantum Universe.

And the area continues to grow. By 2040, lively residential areas, sports and leisure facilities, and shopping opportunities will supplement research, training, and businesses. A cover on the A7 expressway and the relocation of Hamburg’s racing track will allow for the construction of 3,800 new apartments and 2 schools.

The Science City Hamburg Bahrenfeld GmbH is in charge of developing the premises. Its Infocenter offers information for visitors and guided tours around the area. Every Thursday at 6 pm, there are tours for interested members of the public. You do not have to sign up in advance. The free tours start at the Science City Infocenter, Albert-Einstein-Ring 8–10.